Report by William Marcil

Esteemed Members of the Society, I am much touched by the reception I have received here. I hope the following tale shall be sufficient in proving my merit, and serve as initiation into this storied assemblage.

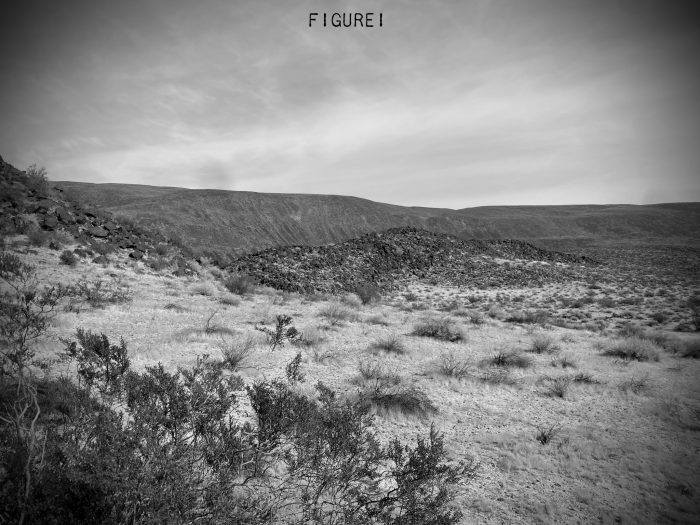

About a month ago, I was looking, out of idle curiosity, at a map of Death Valley and its surrounding environs, when I noticed a site, some miles to the southwest, marked “Black Valley Petroglyph Site.” Intrigued, I researched further, upon which I discovered that the site was part of the Black Mountain Art District, located in and around Black Mountain, California, consisting of well over 11,000 petroglyphs carved within the last 2000 years. I found myself wanting to see them personally, and my curiosity increased when I discovered that in the vicinity was an abandoned mine, from whence once flowed opals to Tiffany & Co.

I decided I would go. Immediately I identified a few problems, first and foremost of which was that the roads leading to the site were entirely unpaved. I do not own a car capable of taking such roads with ease, just a four door sedan, but it had seen me through my city driving, which had been reliably described by my passengers as “terrifying”. Additionally, while there were smaller dirt roads, there were ones large enough that it seemed to me to denote a usage common enough for some actual upkeep, and thus it seemed theoretically possible for my driving at least some distance on them. It also seemed far too much to explore in one day, but, upon conferring with members of Field Station 33, I decided to make my excursion a mere scouting expedition. My mind made up, my route set, I made the necessary logistical purchases, and before sunrise of January 31st, I set off.

My traversal of the paved roads was unexceptional, and a few hours later I found myself barreling past a sign stating “Pavement Ends,” and so it did. I knew I had overestimated my cars ability to handle these roads almost at once. The roads were firm, but for some reason, rippled. The car began jittering, rattling, every piece oscillating at a slightly different rate, threatening to shake apart. I spied a side street, and wanting an end to the vibrations, turned onto it, and immediately got my car stuck in the mud.

I attempted several methods to unstick my car myself, from alternating drive and reverse, to excavating out the tyre, to tying a bit of scrap wood to the wheel to try to give it treads. Nothing worked. Despairing, I wandered down the desolate street until I found a strapping young lad named Ruben who agreed to help me out. Through the vaunted power of teamwork, we got my car unstuck, but I had burned two hours of daylight in so doing. I returned to the main road, and its jittering, and made my way toward the mountain.

The oscillating did not cease as I approached my destination, and, continuing to fear for my car’s suspension I pulled off to the ruins of some sort of plinth on the side of the road. I could see the mountain in front of me, to the north not a mile distant, and I thought I saw the entrance to the Black Canyon. I retrieved my gear, checked my map and compass, and set off.

The landscape around was beautiful. A golden grass covered most of the area, with countershaded bushes growing to about calf and sometimes even chest height. Little taller grows. To the north, overlooking all, was the dark mass of Black Mountain. I realized, much to my delight, I was in the wash of the mountain, and kept my eyes trained to the ground to see what geological delights I could discover. It has been several years since I undertook any serious geologic study, but to my delight, among the pastel coloured rocks I discovered many waxy chalcedonies, jaspers predominating, pieces of quartz and serpintine with porous volcanic rock becoming more common as one approached any rise of geographic note. I quickly started placing any specimen I thought noteworthy in a pouch at my waist, little realising they would be the only real success of the expedition.

I had thought myself but a mile, perhaps a mile and a half distant, from the opening to the petroglyphs. As I crested the first rise, I realized that I was very much mistaken: using my binoculars and consulting my map, I was less that a fourth of the way there.

So on I marched, step after step, foot after foot, minute after minute, the edge of the mountain were I hoped the entrance would be becoming closer as time passed. The beauty of the landscape became monotonous, and my eyes, still trained on the ground, became more occupied looking out for anthills to avoid than rocks to pocket.

Alas! What I thought to be the entrance was merely a turn in the mountain, but I could definitely see the aperture now. It was as far away to me then as where I stood was from my initial position! I considered scrubbing the whole expedition, but I realised I had no choice but to continue. I had to at least make the petroglyphs, from there I could decide about the mine.

I kept going, singing songs from musicals in my head to keep me entertained. I had stopped noticing the grass now, and the rocks in my view were nothing but hazards to be navigated around. 30 minutes passed. On I went. 30 minutes passed. A quick break to rest my legs and eat and drink. 30 minutes passed. The breach, I could start making out details now. I could differentiate the closer side of the gap from the other. Keep going man, you’re nearly there. Is that? Yes! A road! Follow it man, it can only lead one place!

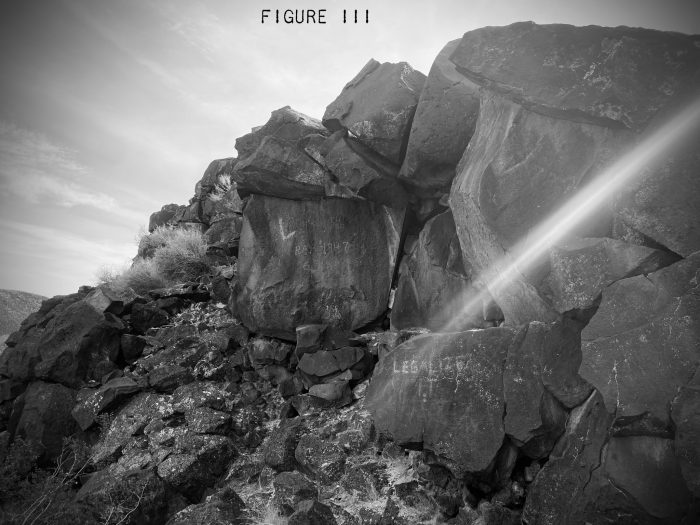

I had made it. I could see the remains of a fire pit and a campsite, set up within the curve of the road. I ate more of my provisions, and finished off one of the two large bottles of water I’d brought. On the other side of the camp, I could see a slight rise, a gap, and then a wall of stone rising out. That, I opined, must be Black Canyon. As I made my way over, I could see, carved on a rock on my side of the gap: a curve with a lightning bolt rising out of it. I sat down, and congratulated myself on making it. I took out my lunch, poured myself a cup of tea, and luxuriated in my accomplishment.

After about ten minutes, I thought about what would come after this. I checked my watch. It had taken me three hours to get this far, and, if my map was correct, it was even further to reach the mine. Unceremoniously I abandoned trying to reach it. “Something for the full expedition,” I thought. However, I realised to my horror that there was only three and a half hours of sunlight remaining. If I didn’t get a move on, and sharpish, I would be trapped in the desert on unfamiliar dirt roads in the dark.

I gathered my belongings quickly, and turned back, following the road out. I saw a rather large ridge in front of me, and made it my target. As I climbed up, I took out my binoculars; perhaps I could see my car from here, and judge the distance. It was not good: my car, even magnified through my binoculars, was the size of a small bead, but I could see it. I took a reading on my compass. If I follow that, I reasoned, and did not deviate, I might just make it in time.

I was indefatigable in my march. No rest, no breaks; if I drank, I drank while I walked, if I ate, I ate while I walked. Where I kept my head down going out, I kept my eyes forward coming in. What took three hours before, through determination and drive took an hour and a half. I made it back to my car with shoulders sore from holding my bags, and my legs screaming from my long forced march. I was in just as much pain as I have ever been, but I had made it. I gave a whoop of joy, as the sun was only just beginning to climb down out of the sky. I quickly hopped in, started the motor, and drove away. As I got on paved roads again, the sun started to go orange.

In conclusion, I believe this is a site of absolute interest to the Society, given the archeological, geological, and possible gemological interests. However, should a full expedition be mounted, I cannot stress enough the necessity of proper planning: vehicles capable of handling the road are a must, and I would expect a full expedition to last three days at least: one load in, one exploring, one load out. The good news on that front is that a majority of the land around the mountain is under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management, and as such (if I understand correctly) one does not need permits in order to set up camp.

I thank you for your attention, and I hope this report has been to your satisfaction.

-William Marcil

Figure I: Black Mountain and surrounding environs.

Figure II: The author resting his weary bones.

Figure III: The Black Canyon Petroglyphs Site. Unfortunately most of the glyphs in this photo are modern additions.